Who cares about data? Tensions between public trust and private interests in health and social care

Data collection and use is integral to several policy documents – enabling better integration of health and care data (and digitisation of social care records) – and it is a topic which is relevant to different research areas in the Centre for Care. However, concerns have been widely discussed in the media; this commentary provides a timely, critical, reflection on such concerns, and suggests that policy aims to improve public trust in data are contradicted by some of the ways that data has been used in recent years.

Combining health and social care data

In November, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) controversially awarded a large contract to Palantir. The contract is to provide software for the NHS ‘federated data platform’ – Palantir is a US ‘spy technology’ firm which has been described by Amnesty International as ‘linked to serious human rights abuses’. While some have welcomed the combining of health and social care data, others are more cautious. Martha Gill in the Guardian describes the move as a ‘medical gamechanger’, offering the opportunity for a more ‘joined up’ system and the development of new treatments.

In contrast, Cori Cryder of the law firm Foxglove refers to the recent development as a ‘four-year blag into the heart of our NHS data’ which has seen Palantir expanding into health technologies. Their platform will aim to connect disconnected data sources not only across NHS trusts, but also across Integrated Care Systems (ICSs), in doing so incorporating social care data. Working with the membership organisation for ICSs, the NHS Confederation, has been part of this ‘four year blag’. Palantir’s UK health leads published an NHS Voices blog on the topic of integrated care, then NHS Confederation commissioning a report ‘supported by Palantir’, and both organisations collaborating on a partnership webinar.

Newly appointed Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Victoria Atkins, announced the award in Parliament with the contention that: ‘safety and security of patient data is front and centre of this new system […] [a]s happens currently, there will be clear rules and auditability covering who can access this data, what they can see, and what they can do’. But trust in such ‘clear rules’ have been undermined by recent public-private deals, which serve particular financial interests as well as providing extensive access to data. For example, the IT company Infosys – which the wife of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Akshata Murty, has shares in estimated at £500 million – has been ‘involved’ in public sector contracts worth £172 million. This includes seven contracts between the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and Infosys which total £16.7 million, with the most recent of these contracts signed on November 7th. This close involvement in public services is despite concerns raised regarding Infosys, including: Sunak’s failure to declare ‘huge wealth’ connected to Infosys in the ministerial register; conflicts over trade talks with India; and a tax dispute between Infosys and HMRC. Infosys’ latest contract with the CQC states that ‘Infosys have access to all kinds of data CQC need to fulfil their legal obligations’.

Workforce data

Information related to workers is another form of data which private organisations might access in health and social care contexts. Providing an instance of this, in 2020, David Cameron lobbied politicians on behalf of the financial institution Greensill – where he was employed and held stock options in the organisation – to access information about NHS employees. He was promoting an app produced by Greensill called ‘Earnd’, in Cameron’s words, ‘an app that allows NHS employees to draw their salary earned, not yet paid, in real time’. Critics described it as essentially payday lending. Earnd was given access to Electronic Staff Records of NHS employees – an arrangement which Cameron said would make the app ‘slicker’. NHS Shared Business Services also entered into an arrangement with Earnd to facilitate rollout into ‘all’ NHS Trusts, but by April 2021 it had gone into administration.

A further use of worker data that faced criticism during Covid-19 pandemic was the ‘Care Workforce App.’ While it was produced by NHSX (the organisation created by former Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Matt Hancock, with a focus on ‘transforming’ the NHS), the system was operated by private technology firm Hive Learning Ltd. The app provided a learning resource for adult social care workers ‘a single one-stop-shop providing the sector with all the latest guidance, wellbeing support and advice they need to protect themselves from COVID-19 and keep themselves well.’ It also signposted users to mental wellbeing apps – Sleepio, Daylight, and Silvercloud. The app was criticised by the union GMB, with national secretary, Rehana Azam, arguing ‘bosses can quite easily use it to spy on workers, see what they’re saying and potentially sanction them’.

‘Good’ and ‘bad’ data use

More recently, there has been a ‘scandal’ related to the use of data for research purposes concerning biomedical database UK Biobank, which contains genetic and health data of half a million volunteer participants. UK Biobank is supported in various ways by the Government: in October, the Government pledged to match a £16 million donation to the organisation. NHS England also endorsed a letter sent by UK Biobank to GP practices asking for access to ‘relevant data.’ As with the partnership with Palantir, the benefits related to sharing data were by some advocated, with the Guardian’s Polly Toynbee publishing a column arguing that ‘privacy fears’ were stunting the potential of data held by UK Biobank and calling on the BMA to encourage GPs to ‘hand over our data’. However, the concerns of, e.g., GPs, do not appear to be unfounded: in November, an Observer investigation found that data held by UK Biobank had been shared with insurance firms despite initial promises that ‘[i]nsurance companies will not be allowed access to any individual results nor will they be allowed access to anonymised data’.

An interesting aspect of Toynbee’s article is that she sets up a distinction between ‘good’ data use, i.e., for research, and ‘bad’ data use, by decrying the Government’s arrangements with the untrustworthy Palantir. The UK Biobank revelations demonstrate how precarious it is to rely upon individual, for-profit private organisations to ‘behave’ themselves when it comes to data. It is also an approach which increases risk, regardless of the behaviour of the provider – indeed, Gill’s Guardian article closes by questioning whether Palantir has sufficient capacity. Gill quotes Simon Bolton (former chief executive of NHS Digital), saying: ‘this is a single deal with one consortium […] there’s quite a lot of risk that it goes wrong’. These issues of precarity should be contextualised within a lack of broader regulation. There has, for example, been a general watering down of the DHSC’s approach to data. In September the Government updated the ‘DHSC privacy notice’ to include a section on automated-decision making or profiling (which it connects to efficiency) with certain key points deleted. Trendall (2023) describes these omissions in a passage worth quoting in full:

In the previous version of the policy, the DHSC committed that it would “not make your personal information available for commercial use without your consent”.

This provision has been entirely removed.

The guidance also formerly contained a pledge that “the data we are collecting is your personal information and you have considerable say over what happens to it”.

This has been amended to simply “the data we are collecting is your personal data”.

Such changes undermine the policy aim of ‘putting public trust and confidence front and centre of the safe use and access to health and social care data’, as outlined in the policy paper Data saves lives: reshaping health and social care with data. It is a policy paper which is hyperbolically titled, as data must also be acted upon. Based upon the recent approach to data, it would, perhaps, be more accurate to contend that data ‘makes money’ – in ways which increase risk of failure in how data is collected and used, and decrease levels of public privacy and trust.

About the author

In her role at the Centre for Care, Grace will be working with Dr Kate Hamblin to examine the effects of technology changes on paid and unpaid care provision. The research will consider whether, and in what circumstances, digitalisation has positive or negative consequences for stakeholders. It will focus on inequalities of technology implementation, the impact of fragmentation and financialisation, and the nature of the labour process.

More commentaries

Lucy Wood writes about the recent Carer’s Trust all day event – Caring Across London: Collaborating for change.

Read More about Carers Trust: Caring across London

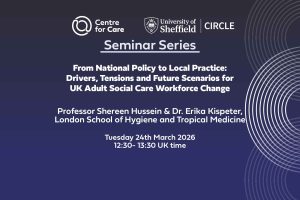

We are delighted to virtually welcome Professor Shereen Hussein and Dr. Erika Kispeter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to present for us on 24th March 2026.

Read More about Seminar: From National Policy to Local Practice: Drivers, Tensions and Future Scenarios for UK Adult Social Care Workforce Change

Towards a better future for care: impactful events Fay Benskin and Dan Williamson discuss some of the key recent impact events which the Centre for Care have hosted and/or been involved in. They reflect on policy breakfasts at the House of Commons which focussed on Carer’s Allowance reform and the evidence in support of Paid […]

Read More about Podcast: Impact miniseries episode one

We are very pleased to launch our new impact report today, ‘Towards a better future for care’.

Read More about Towards a better future for care: Centre for Care Impact report (November 2021-April 2025)