What does it mean to describe social care as an ecosystem?

By Emily Burn and Catherine Needham

In this commentary, we explore what it means to describe social care as an ecosystem. We outline the key features of the concept, consider the complexity of social care and discuss its implications for policymakers and practitioners.

This is the first of a series of commentaries outlining how policymakers and practitioners can use the concept of ecosystem to navigate the complexities of social care. In companion commentaries we will look at how to generate change in the social care ecosystem and how we think about the resilience, or the wellbeing, of the social care ecosystem.

Social care is often described as a system – we know that the planning and delivery of social care involves a multiplicity of people, organisations and resources. The social care system provides support to older and disabled people, people with a long-term mental health condition and unpaid carers. It encompasses support funded by the state, support people pay for themselves, as well as support from families and the community. Each part of the social care system is interdependent, relying on other parts to provide appropriate and effective care and support. The functioning of social care is also linked to other systems. Healthcare and housing are just two examples where there are strong connections with social care – decisions made in each of these sectors will affect social care and vice versa.

At the Centre for Care, we use the term ecosystem as a holistic way to encompass all the organisations and people involved in social care. While this is a metaphor rooted in ecology, it is a term that can help us to understand the interdependencies of social care, as well as thinking about which factors help the overall system to function well.

What do we mean by an ecosystem?

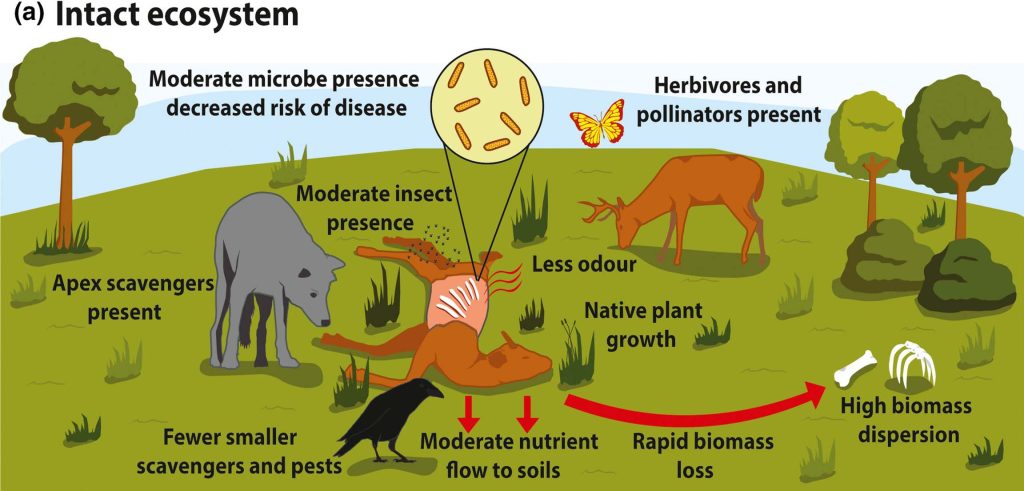

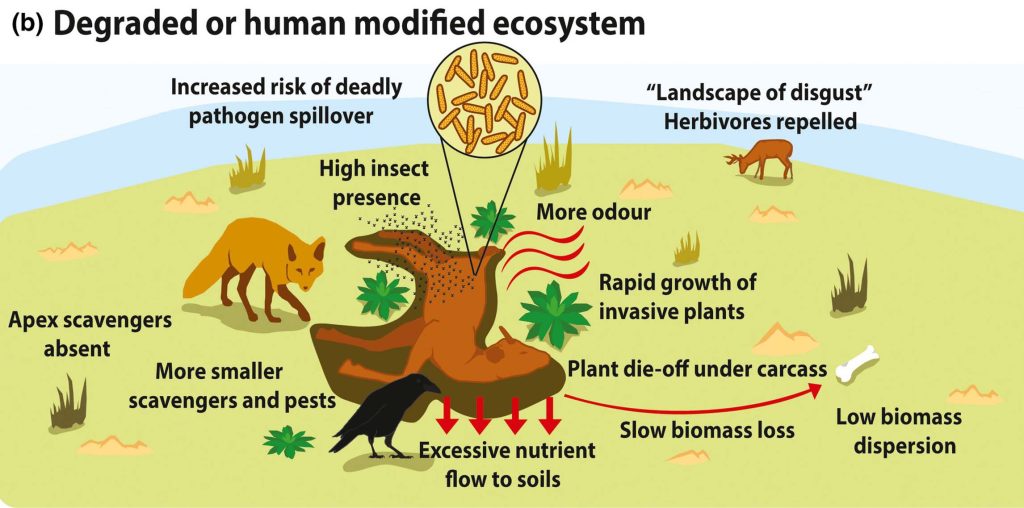

The images below can help us to understand why the metaphor of an ecosystem is useful. The images show an ecological landscape, demonstrating how the parts of an ecosystem interact and influence one another.

This picture depicts a healthy ecosystem. Here, the constituent parts of the ecosystem interact in ways that lead to a robust and sustainable interdependence.

The second picture below reflects a damaged ecosystem where the positive interdependencies have been lost. The constituent pieces are no longer appropriately balanced, to the detriment of the ecosystem as a whole.

We use these simple images as an alternative to the sorts of complex flow diagrams which can sometimes be used to capture a whole ‘ecosystem’ within public policy. One of the features of social care is its complexity: within the UK alone there are hundreds of thousands of people using services, over a million paid care staff, millions of unpaid carers, thousands of provider organisations, hundreds of local authorities commissioning services, in partnership with health, housing and other organisations. Even within a single local authority or a neighbourhood, the number of people and organisations within an ecosystem soon reaches a level of complexity that is impossible to map. Attempts to chart the ecosystem for complex policy issues such as the famous Foresight obesity system map have been seen as overwhelming, contributing to fatalism and inaction.[1]

The simplified landscapes shown above offer an alternative way of visualising the ecosystem which nonetheless highlight some key elements of the ecosystem metaphor:

- No one is controlling the whole system or shaping it to ensure equilibrium. The equilibrium comes from the positive interdependencies between the different elements.

- The animals and microorganisms are not deliberately trying to help each other, and indeed may have conflicting agendas (predators and prey), but together their interactions influence the wellbeing of the ecosystem.

- Past events and behaviours shape what is happening now (e.g. food availability).

- Degradation may be difficult to see until it is well advanced, and its causes may not be easily understood.

- The hillside shown in the image is only one part of an ecosystem which can be looked at on a much larger or much smaller scale.

Applying the ecosystem concept to public policy

These points have applicability to public policy contexts too such as social care, although we need to make some adjustments: policy-makers are attempting to influence the social care ecosystem, using laws, resources and incentives. The social care ecosystem is shaped by these interventions. However as Dessers and Mohr note when writing about integrated care, a care ecosystem is like a natural ecosystem in the sense that it is not generated by these intentional efforts: ‘it is always already there’.[2] This is an important insight in relation to social care, for two reasons. First, it is a reminder that we are never at the beginning of ecosystem design. Just as past behaviours and events shape the natural ecosystem, so in a social care context there are existing relationships, resources, laws, buildings, borders, etc, that shape the effectiveness of any intervention. The influence of the past – sometimes called ‘path dependence’ – can make it difficult to bring about change, at least in predictable ways. System shocks, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, will disrupt the ecosystem and their impact may take a long time to be clearly understood.

Second, the ‘already there’ aspect of ecosystems is a reminder of the universality of care in human communities: social care ecosystems are shaped by policies and professional practices and will vary from state to state but they predate and exist beyond these policies. The universality of care does not of course entail that their current form – e.g. the gendered distribution of care – should be taken as somehow naturalistic and inevitable. But it does highlight the need for policymakers to exercise caution and humility when intervening in an ecosystem to avoid contributing to the kinds of degradation that we see in the second image.

Just as the hillside is only one part of a bigger ecosystem, a further factor to consider in relation to social care, is what is the appropriate scale at which to engage with the ecosystem, and how and where it intersects with other systems. For the natural ecosystem we can imagine zooming in to see the microbes in the soil or zooming out to see varied landscapes and bigger influences at work, e.g. weather patterns. In social care, we could consider the ecosystem at the level of the local authority, perhaps examining elements such as the commissioning practices, the assessment processes and support for direct payments. But we could also zoom into the level of the individual using services and the ecosystem of formal and informal care that surrounds them. Conversely by zooming out, we might consider how bigger factors such as the local labour market or the availability of affordable housing shape the viability of the ecosystem. Much of this may be beyond the control of social care policymakers. For example, the builders of a new retail park in a locality may be creating jobs which draw workers away from social care, or the closure of a large employer might lead to family members moving away and no longer being able to provide unpaid care to a parent.

For policymakers, trying to intervene effectively in ways that support rather than degrade the ecosystem, this complexity can make it difficult to know how to proceed. The interdependencies can be hard to see and predict, and indeed may lie beyond their remit. Writing about complexity in public policy, Room describes this as ‘policy-making played out on a bouncy castle, whose topography is itself being continually transformed…’..[3]

Three ways for people to shape the social care ecosystem

1. Articulate the social care equivalent of an ‘intact’ ecosystem (image 1 above). An ecosystem might be one that supports ‘flourishing lives’ or which works to realise the #socialcarefuture vision: ‘We all want to live in the place we call home, with the people and things that we love, in communities where we look out for one another, doing things that matter to us’. Members of the Centre for Care Voice Forum and the University of Birmingham Lived Experience Panel people talked about a well-working social care ecosystem as including elements such as:

- Timely and accessible information and advocacy

- Fair eligibility criteria

- Responsive assessment processes

- Appropriate care and support plans

- Access to direct payments or personal budgets when wanted

- Choice of provider

- Adequate support for unpaid carers

- Adequate funding for providers and staff

- Investment in community support capacity

- Coordinated health and social care

Considering the elements of a well-functioning ecosystem also provides a moment to reflect on the elements which are preventing the ecosystem from flourishing: are they about flows of resources, information or conflicting values? In writing a book on Social Care in the UK’s Four Nations, Needham and Hall found that there wasn’t a clear consensus on which values should be prioritised: was the emphasis on keeping people safe through regulation, professionalisation and standardised services (no post code lottery!)? Or was it about giving people maximum choice and control, even where that created risks and geographic inconsistencies? In the book we concluded that policymakers in local and national governments needed to engage directly with the trade-offs between these values and what should take precedence in the event of a clash. These conversations could be had in localities with communities and people with lived experience to understand better the patterns of positive interdependencies and how they can best be sustained.

2. Recognise that the ecosystem has different levels, and that different forms of intervention might be relevant for different levels. In the natural ecosystem metaphor we can helpfully distinguish between different scales into which we can zoom in or zoom out. We can do the same thing in a social care ecosystem. Thinking about the structure of the social care ecosystem encourages us to consider how resources flow across and within each of these nested levels. We can think of the social care ecosystem are having three levels.

- The micro level encompasses people accessing services and their interactions with peer support, community activity, unpaid carers and formal care providers.

- The meso level includes local and regional agencies. Here, we can find social care providers and local authorities, as well as health services.

- The macro level encompasses national agencies and would include national government policy affecting the delivery and access of social care.

Figure 1: Ecosystem levels. Adapted from Frow et al.[4]

3. Prioritise building trust and relationships. Unless we build relationships that recognise the interdependencies, mutual reliance, and potential conflicts we cannot be working towards a robust ecosystem. This needs to happen at all levels of the ecosystem. It should be a priority for the policymakers and senior leaders who are intervening in the system at the macro level, working through existing institutions like local authorities, and creating new institutions like Integrated Care Boards. Helen Bevan has written about how system transformation can only proceed at ‘the speed of trust’. Bill Banneer takes an approach which he calls ‘centring relationships’. He describes this as moving ‘away from designing the thing, to designing for the emergence of the thing, driven by the formation of the necessary relationships’.

At the meso level, the commissioners, providers and communities who are shaping care need to also attend to their relationships. New approaches to commissioning social care offer a way to build relationships differently. The use of alliance contracting, for example, provides an alternative to traditional tendering processes. Alliance contracting is when a group of providers are commissioned to deliver a service. The Human Learning Systems team offer a worked example here from Plymouth along with an example contract. Conversely, when relationships are seen as expendable or a ‘nice to have’, they are constantly severed and remade in the search for efficiency. In a project on care market shaping, we found that local authorities were cycling between commissioning approaches. They went from ‘let’s have a small market of big providers’, to ‘let’s have a big market of small providers to improve choice and control,’ and then concluded, ‘that’s too complex to manage, let’s shrink back down to a few big providers’. Each of these turns around the cycle takes years and requires a severing and rebuilding of relationships and a squandering of trust.

At the ‘micro’ level of people living in communities and drawing on support, the importance of relationships is obvious although often degraded by formal services. Bryony Shannon’s blog on ‘rewilding’ social care focuses on the need to move beyond fixing individuals to supporting relationships: ‘We need to identify and strengthen people’s roots by shifting our focus to building, maintaining and restoring connections. We thrive through our relationships – we need to support them to flourish.’ The work of Hilary Cottam in Welfare 5.0 powerfully articulates a new approach to social care which starts with relationships.

What does this mean for social care policymakers and practitioners?

This introduction to the social care ecosystem highlights several areas for further exploration.

- What would a flourish social care ecosystem look like? What would be the appropriate indicators of flourishing?

- What are the barriers to realising that at the micro, meso and macro levels?

- Which localities and organisations are intervening effectively to enrich their social care ecosystems? How can that learning be best shared and grown?

The Centre for Care is engaging with these questions through its theme ‘Care as a complex adaptive ecosystem’. In local case sites, we are looking at how we can capture and assess the connections between the different parts of the ecosystem. We are also exploring what we mean when we describe a social care ecosystem as well-functioning, who does the social care ecosystem function for, as well as identifying the factors that contribute to a well-functioning social care ecosystem.

You can read our review of the academic ecosystem literature here in our new working paper.

We will publish further commentaries on this topic as our thinking develops, reflecting the findings of our fieldwork. For further information contact Emily Burn e.burn@bham.ac.uk.

References

[1] French, M., Hesselgreaves, H., Wilson, R., Hawkins, M. and Lowe, T. (2023) Harnessing Complexity for Better Outcomes in Public and Non-Profit Services. [Online]. Available: https://library.oapen.org

/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/61202/1/9781447364139.pdf

[2] Dessers, E. and Mohr, B. J. (2019) ‘Integrated Care Ecosystems’, in Mohr B. J. and Dessers, E. (eds.) Designing Integrated Care Ecosystems. A Socio-Technical Perspective. Cham: Springer Nature, p. 20-21.

[3] Room, G. (2011) Complexity, Institutions and Public Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 7.

[4] Frow, P., McColl-Kennedy, J. R. and Payne, A. (2016) ‘Co-creation practices: Their role in shaping a health care ecosystem’. Industrial Marketing Management, 56, 24-39. DOI: https://dx.doi.org

/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.03.007.

Emily is based at the University of Birmingham where she is focusing on exploring the application of systems thinking to the analysis of social care. Prior to this role, Emily was part of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded project at the University of Birmingham exploring local authority market-shaping activities in social care and how these facilitate the development and access of personalised care and support.

Catherine Needham is Professor of Public Policy and Public Management at the Health Services Management Centre, University of Birmingham. Her research focuses on adult social care, including personalisation, co-production, personal budgets and care markets. She has published a wide range of articles, chapters and books for academic and practitioner audiences. Catherine led the Care in the Four Nations work package within the ESRC Sustainable Care team. She is now leading research on care systems as part of the ESRC Centre for Care and is also a member of IMPACT, the UK centre for evidence implementation in adult social care. She tweets as @DrCNeedham.

More commentary

Centre for Care Researchers Lucy Wood and Becky Driscoll analyse the recent policy discussions around welfare reform in the UK, exploring at the Universal Credit Bill and the Pathways to Work Green Paper published in March 2025.

Read More about Pathways to Work or Pathways to Poverty? The Risks of Welfare Reform for Disabled People and Carers

Professor Shereen Hussein reflects on attending the Symposium on Global Ageing, emphasising the need for equitable and sustainable care systems.

Read More about From the Vatican to Workforce Change: Reflections on Global Ageing, Dignity and the Care Economy

Professor Nathan Hughes responds to the UK Government’s 2025 Spending Review in relation to children’s social care.

Read More about Can New Money Shift Old Systems? What the 2025 Spending Review Might Mean for System Change in Children’s Social Care

The Centre for Care team respond to last week’s 2025 UK government Spending Review.

Read More about Left on the Back-Burner: Adult Social Care and the 2025 Spending Review