Carers’ Financial Wellbeing

Most people are carers at some point in their lives. The average person is just as likely to be an unpaid carer as a home owner in the UK. Caring for a loved one can be fulfilling and meaningful, but without proper support providing unpaid care comes at a financial cost. People can find themselves worse off financially if, for example, they are unable to work full-time because of their caring responsibilities, or if they have to give up work altogether. People who provide unpaid care can also face a range of other expenses affecting their income, savings, and wider financial circumstances. These expenses might include things like transport costs and hospital parking charges, home adaptations/specialist equipment, and higher utility and shopping bills. But these costs only tell part of the story. The subjective experience of caring and how caring shapes a person’s sense of financial wellbeing is equally important. Financial wellbeing is not just about quantifiable measures such as income, debt, and money in the bank, it is also about whether a person feels financially secure, in control, and free from stress and anxiety. It is also about whether they can make plans for the future that align with their goals and expectations and whether they have peace of mind. The study reported on here is the first to apply subjective notions of financial wellbeing directly to the experience of care and caring and with an emphasis on capturing and understanding changes in carers’ financial lives over time.

Our study

We interviewed 50 unpaid carers ranging in age from 21 – 88, including a variety of caring relationships. Some participants were caring for parents, some for spouses or ex-spouses, some were caring for siblings and others were caring for their children with complex health needs. We asked participants about their experiences of caring, the financial costs of caring and about their current financial circumstances. We also asked about their plans and aspirations for the future, to explore how and why caring might impact those plans, and to understand any potential risks to current and future financial wellbeing. We conducted critical event timeline interviews with a subset of participants to get a better understanding of their sense of financial wellbeing over time.

What Are Critical Event Timelines?

Critical Event Timelines are a visual representation of changes across a life course, where key events and transitions are recollected and mapped out in chronological order. Timelines have been used to explore many different aspects of people’s lives, such as illness journeys, youth studies and teacher careers, but this is the first study where timelines have been used to understand carer financial wellbeing.

One key benefit of this method is that it is flexible. Research participants create their own timelines independently from the researcher, acknowledging that people are the experts in their own lives. Participants decide what they will include on the line, and therefore what the interview will focus on. In the subsequent timeline interview participants talk through life events on the timeline, locating them in a particular place and time, and outlining the context and circumstances.

Unpaid Carers’ Financial Wellbeing Timelines

We asked unpaid carers to plot key events that had influenced their sense of financial wellbeing over time, such as the beginning (or end) of an important relationship, job changes, starting a family, financial gifts, retirement, and transitions in and out of caring. By mapping these events in chronological order, timelines can reveal when, how and why a person’s sense of financial wellbeing changes over a life course.

When carers talked us through the timeline, we were able to understand not just what happened, and why, but how it felt. The timelines below illustrate both positive (peaks) and negative (dips) influences on financial wellbeing, highlighting both financial resilience and vulnerability.

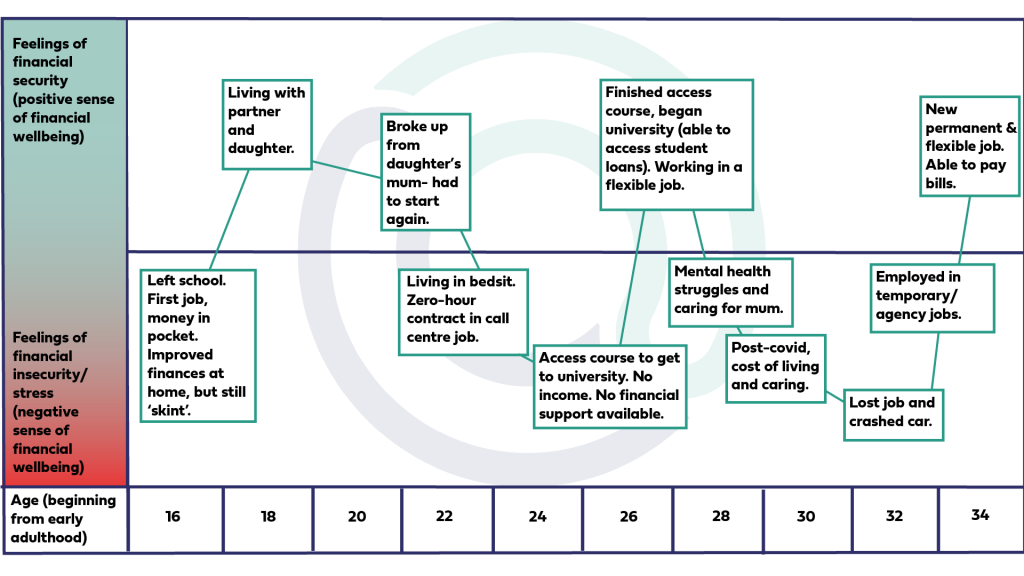

Cam, 32, caring for his mum (carer in early adulthood)

Cam was caring for his mum who had suffered with poor physical health since he was young. He described the estate he grew up on as ‘a stereotypical socially and economically deprived area, with not many opportunities’ He left school at 16 and started working to help his mum with bills. He talked about feeling proud that he was earning money and contributing to the household.

‘Some of the money I still kept to myself, so in terms of a 16-year-old, you know, even though we were skint, and I was giving my mum money, I still had a bit more money than some other people because I had a job. Even though I was doing it because I had to … But we were skint.’

Cam said he had ‘floated through’ a succession of low paid, insecure jobs since leaving school.

‘I left school with nothing really, like I said, I never pursued college just started work straight away. I was like a class clown. I didn’t engage with my studies whatsoever. Stereotypical story I guess, from lads from that area.’

Following the birth of his daughter, the subsequent break up of his relationship was a low point for Cam. Hoping for positive changes he decided to complete an access course and go to university as a mature student.

‘This was like a hard reset in my life, really. I had nothing, like, I had to literally start again.’

Although many young adult carers are unable to progress to, or complete, higher education due to their caring responsibilities, Cam managed to juggle his conflicting roles, and despite the ‘strain’ successfully completed his degree. After leaving university, the demands of managing paid work with his caring role were challenging for Cam. Although he had managed to gain a degree, which should have increased his earning potential, Cam’s caring responsibilities were interfering with his ability to find graduate level employment.

‘So, I was delivering for the Royal Mail for a little bit, and then I started working at [supermarket] in HR and I actually really enjoyed that because I made loads of good mates, and I could work from home. But that was a six-month temporary contract … But that’s the pressure of life … I couldn’t afford any time off because I have so much to pay out. And then you fall into the trap, taking a job you don’t want.’

Cam’s low income meant he was unable to save for a short term or long-term future, and he often relied on credit. Along with many others in the cohort who reached young adulthood during times of austerity, Cam was living in private rented accommodation, with little hope of saving for a deposit and getting a foot on the housing ladder. The additional challenge of caring meant that Cam was in a financially precarious situation that could permanently impact his income, wealth and health trajectory, and he was worried about the future.

‘I think the caring, you know, runs that risk [financial insecurity] because my mum has a physical disability that’s only going to get worse with age, you know? So, she’s coming up to 64. So, she’s not even that old, you know? What’s it gonna be like in 6-10 years? You know, when she’s, really knocking on. So, there’s always that like in the back of my mind, I’m thinking, you know, this is how it is now, what’s it gonna be like then?’

In our final interview with Cam, he had been able to secure flexible permanent employment, meaning he was better able to manage his caring role alongside paid employment, but was still struggling with his own wellbeing.

‘I’m trying to spin so many plates, it’s just, it can still be a bit suffocating.’

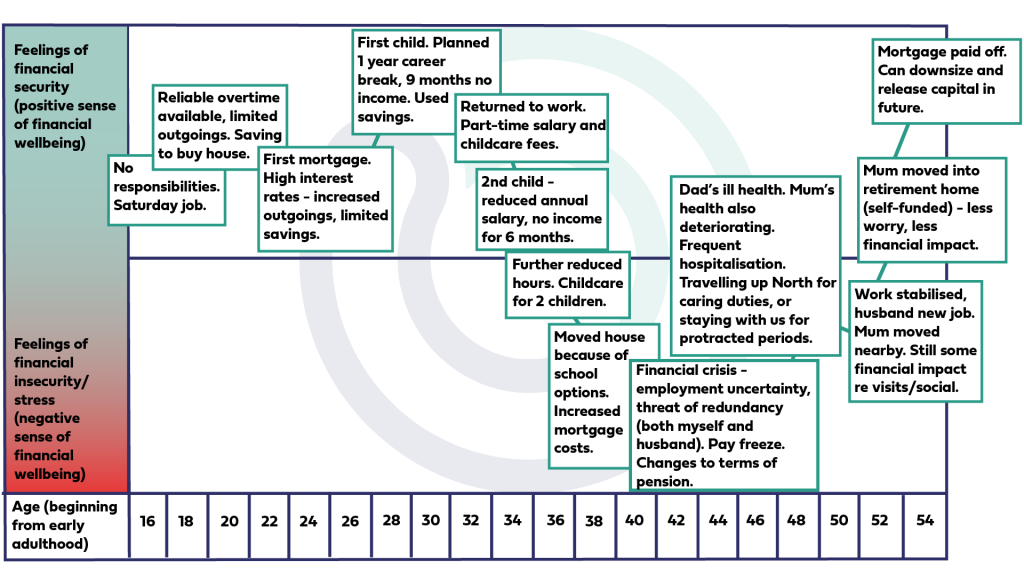

Emily, 54, cares for her mum (carer in middle adulthood)

Emily’s timeline reveals that before she began caring for her mum there were several life events that had a negative impact on her financial wellbeing, such as reducing her working hours after her first and second child. During the interview, Emily reflected on the impact this period had on her pension contributions, and her future financial wellbeing. She admitted that she never considered the financial impact until she was closer to retirement age.

‘…And in fact, it’s only now when, you know, a few years off retirement, and looking at pension calculators and that sort of thing, realising actually, [caring] had a huge impact. Because by the time I retire, I’ll have probably done 40 years of service, but I will probably have only had 25 reckonable service, which, yeah, it’s gonna have a massive impact on the pension that I can draw. But back then it wasn’t even a consideration’

This illustrates the cumulative costs that unpaid caring can have over a life course.

Alongside a reduced salary and reduced pension contributions, Emily talked about the out-of-pocket expenses related to caring:

‘Probably the biggest cost is petrol. There’s also, because Mum doesn’t get out of the house without, or out the flat without me, she’s not able to, she’s not steady enough and her walking, she couldn’t access public transport or anything like that, so she relies on me solely. And I’m very conscious that she’s in the house, the flat, on her own a lot of the time … I like to bring her back here, just so she’s got a change of scenery, so that’s doubling the petrol because it’s there and back, there and back’

Having bought their first house in the 1990s, Emily felt a sense of security from the mortgage being paid off, and the ‘ridiculous price increases’, which meant their family home had significantly increased in value. Emily was comforted by the knowledge that, if necessary, they could move house and release some of the equity:

‘…obviously we’re sitting on quite a nest egg, and I think we will move at some stage, but it’s difficult for me to think about moving while Mum is still here, because she’s only 15 minutes from me and what I don’t want to do is pack up and move out somewhere further out, quieter and cheaper while Mum is still around’

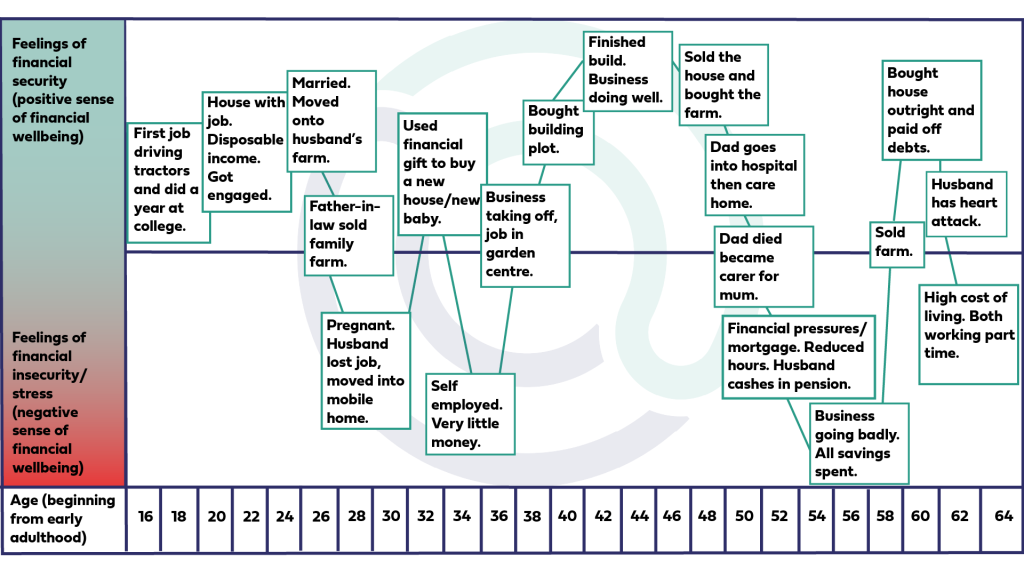

Rosie, 62, cared for her mum (caring in later adulthood)

Rosie cared for her dad and then her mum. While these periods of caring had a negative impact on her sense of financial wellbeing, there were other events earlier in life, such as her husband losing his job while she was pregnant and receiving a low income while self-employed, that also had a negative impact. On the other hand, receiving a financial gift and being at a stage in life where the mortgage was paid had a positive influence.

Although Rosie had plans to downsize to release equity in the house, she had concerns about their future finances as her husband had cashed in an old pension to release some funds when they were under increasing financial pressure

‘…he paid into it a year after we got married. So he was about 25/26. So yeah, it wasn’t a lot. He only paid… I think we paid about one hundred pounds a year, but he made about 30,000’

Rosie had no pension savings of her own and was working part-time to provide an income until her state pension kicked in.

‘I’ve never been able to afford it. Just, you know, the state pension, I presume that’s it.’

Looking back over her life, Rosie reflected that owning a family business had presented uncertainty and financial challenges that, with hindsight, they could have avoided.

‘I mean, if we’d just worked, got a job, both got jobs there, and we would have been much better off. You know, and our daughter … if the three of us had got jobs, we would have been, well, really well off. But yeah, you know, it’s that sort of thing. It was a big mistake. I mean, we’ve always just got by. You know, we’ve always worked hard and it’s just, you know, things happen don’t they and you struggle a bit more’

Rosie felt that persistent increases in the cost of living, in addition to past financial decisions, meant the family would continue to struggle financially in the future but, like Emily, she was comforted by the knowledge that they had equity in their house.

‘So, we probably haven’t got as much money as we hoped we’d have when we were getting to this sort of age, but there are a lot of people worse off … And, we know we’ve got… if we need to, we can sell the house and fall back on that.’

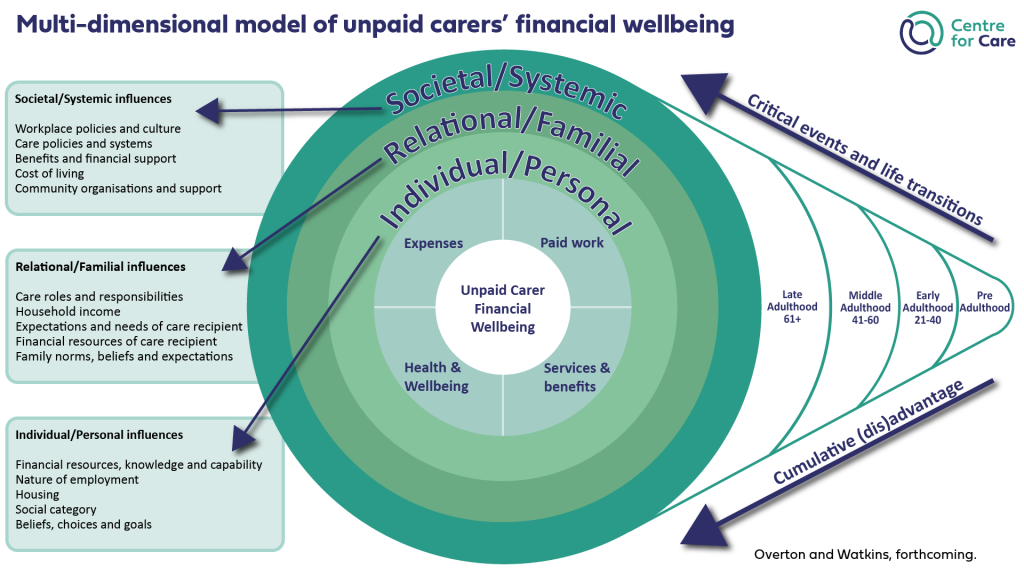

What Timelines Reveal About the risks to carers’ financial wellbeing

These timelines illustrate that while care-related costs present a financial risk to all carers, each individual life course can make individuals more or less resilient to the economic impact of caring, showing that financial wellbeing is a long-term and cumulative process (Kendig & Nazroo, 2016), impacted by influences at personal (e.g. financial resources, nature of employment, housing), relational (e.g. care roles and responsibilities, household income) and societal levels (e.g. workplace policies and culture, benefits and financial support, cost of living).

We identified four key risks to unpaid carers financial security and wellbeing:

- Direct expenses (e.g., travel, home adaptations) reduce disposable income, especially harmful for carers on low incomes without savings.

- Employment challenges (reduced hours, job loss) limit income, savings, pension contributions, and career progression.

- Health and wellbeing can be influenced by the financial stresses associated with caring, in addition to the physical and emotional strain.

- Barriers to accessing support and benefits such as Carer’s Allowance are often inadequate, difficult to access, and stressful to claim.

Our findings also highlight that these risks to financial wellbeing do not exist in isolation. They can overlap and intensify depending on the carer’s life stage and their existing financial circumstances.

- Cumulative disadvantage: Financial disadvantages such as low paid insecure employment, unaffordable housing or repeated caring responsibilities in early and middle adulthood can compound losses in income, savings and pensions over decades.

- Cumulative advantage: Carers with higher incomes who have accumulated savings or assets in young and middle adulthood are better able to absorb financial shocks later in life.

- Critical events and life transitions such asarelationship breakdown, starting a family, job changes and financial gifts shape financial wellbeing not just in the short-term but across entire life trajectories.

We drew on an ecological life-course approach to financial wellbeing (Salignac et al., 2020), recognising that that an individual’s financial circumstances develop in interaction with their environment. The model below represents the complex and dynamic interactions that influence unpaid carers’ financial wellbeing.

Why This Matters

Understanding carers’ financial wellbeing has real-world implications for social care policy, care services, and people’s working lives. If policy makers continue to consider only the short-term financial impacts of caring such as reduced income, the level of Carer’s Allowance, or how many hours of productivity might be lost, they risk failing to adequately address the bigger picture of financial insecurity and inequality across a life course.

By showing how the cumulative costs of caring shape and compound financial wellbeing over the medium to long term, timelines can help policymakers to consider and design support that reflects the impact of caring across a life course. That could mean providing flexible benefits and services that adapt to carers’ changing circumstances, creating employment and pension policies that allow carers to either stay in employment or take on a caring role without sacrificing their long-term financial wellbeing.

Perhaps the greatest strength of critical event timelines is that they don’t just generate data, they give carers space to reflect, to make sense of their own journeys over a life course, and to be heard.

Conclusion

Providing care for a family member or friend shouldn’t come at the cost of carers’ financial security or peace of mind. By using critical event timelines, we can better understand the direct costs of care, as well as the lived experience of managing finances, juggling paid employment with care responsibilities, and the individual, relational and societal influences on financial wellbeing over time. Critical event timelines map key events and contexts, but they also highlight the circumstances that create vulnerability and resilience and can help us to understand the ways that our social and economic systems either fail or support those who care. If we want a fairer future for carers, it starts by understanding their lived experiences and their journeys over time.

References:

Chen, A. T. (2018). Timeline drawing and the online scrapbook: Two visual elicitation techniques for a richer exploration of illness journeys. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917753207

Gramling, L. F., & Carr, R. L. (2004). Lifelines: A life history methodology. Nursing Research, 53, 207-210. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200405000-00008

Keating, N., Fast, J.E., Lero, D.S., Lucas, S.J., & Eales, J. (2014). A taxonomy of the economic costs of family care to adults. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 3, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2014.03.002.

Kendig, H., & Nazroo, J. (2016). Life course influences on inequalities in later life: Comparative perspectives. Population Ageing, 9, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-015-9138-7.

Kettell, L. (2020). Young adult carers in higher education: the motivations, barriers and challenges involved–a UK study. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(1), 100-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1515427

Looman, W. S., Eull, D. J., Bell, A. N., Gallagher, T. T., & Nersesian, P. V. (2022). Participant-generated timelines as a novel strategy for assessing youth resilience factors: A mixed-methods, community-based study. Journal of Paediatric Nursing, 67, 64-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2022.07.025

Overton, L. & Watkins, M. (2025) Understanding the lived experience of unpaid caregiving and risks to financial wellbeing [under review in Journal of Social Policy]

Petrillo, M., Valdenegro, D., Rahal, C., Zhang, Y., Pryce, G., & Bennett, M. R. (2024). Estimating the cost of informal care with a novel two-stage approach to individual synthetic control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.10314.

Riitsalu, L., Atkinson, A. & Pello, R. (2025) Beyond Money – Exploring financial wellbeing through a human lens, Vienna: Erste Foundation. Accessed online – https://www.erstestiftung.org/app/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/FWB_ENG_ePublication.pdf

Salignac, F., Hamilton, M., Noone, J., Marjolin, A., & Muir, K. (2020). Conceptualizing financial wellbeing: An ecological life-course approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 1581-1602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00145-3

Spicksley, K. & Watkins, M. (2020). Early-career teacher relationships with peers and mentors: Exploring policy and practice. In Kington, A. & Blackmore, K. (eds) Social and Learning Relationships in the Primary School, 93-116.

Watkins, M., & Overton, L. (2024). The cost of caring: a scoping review of qualitative evidence on the financial wellbeing implications of unpaid care to older adults. Ageing & Society, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X24000382

Zhang, Y., & Bennett, M.R. (2019) Will I care? The likelihood of being a carer in adult life. London: Carers UK https://www.carersuk.org/reports/will-i-care-the-likelihood-of-being-a-carer-in-adult-life/

Maxine has an interest in human development, behaviour and the decisions that people make across a life span. In particular she is interested in the key influences on decisions that people make in relation to their personal and professional lives.

Louise is Associate Professor of Social Policy in the Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology at the University of Birmingham, and Director of the Centre on Household Assets and Savings Management (CHASM). Louise’s work focuses on understanding and addressing the risks, challenges and inequalities associated with the financialisation of later life in three key policy areas: housing equity, pensions and long-term care.